2024 NPS Preserves Regulation – the latest in a long history

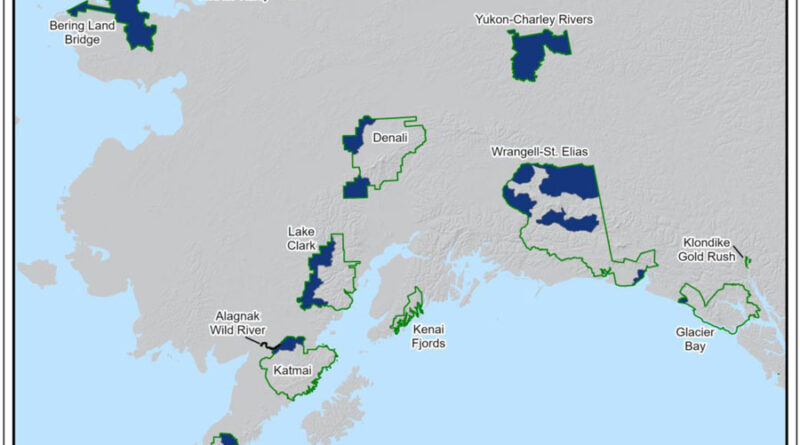

Alaska’s national preserves, created by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA,1980), are unique in allowing sport (non-subsistence) hunting within their boundaries. The 20 million acres of preserves (click map for larger view) were established in recognition of the cultural importance of hunting and trapping in Alaska. ANILCA directed that sport hunting and trapping be managed in the preserves under state regulations (established by the Alaska Board of Game in a public process). Denali’s two preserves are located along the western boundary of the park in rural, sparsely populated areas.

State and federal interests fundamentally conflict regarding key aspects of wildlife management on the preserves. Over the past decade, three attempts to balance these interests using federal regulation have led to time-consuming public process, litigation, and political manipulation. We are hoping that the recently-finalized 2024 Rule, Alaska: Hunting and Trapping in National Preserves, will provide a strong foundation and minimize future controversy. It took a while to get there. Read on for some history.

Emerging conflict – Federal and State wildlife management visions

Shortly after ANILCA was passed, the NPS Regional Director and the Commissioner of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) signed a Master Memorandum of Understanding stating that the two agencies would work together, recognize each other’s priorities, and collaborate whenever possible. Over the succeeding thirty years, the differing missions and priorities of NPS and ADFG strained the spirit of collaboration to the breaking point. In particular, after adoption of the Intensive Management law in the mid-1990s, ADFG managers and Board of Game members adopted an “abundance management/hunter opportunity” mindset. This encouraged hunting and trapping regulations (methods and means) that emphasized predator reduction, including expansion of seasons/bag limits for wolves and bears and expansion of brown bear baiting. In addition, there was ongoing authorization of “non fair chase” activities such as den-hunting of black bears, shooting of swimming caribou, and hunting black bears with dogs. The conflict between the federal vision of protecting intact populations and natural processes was on a clear collision course with the state vision of manipulation for predator reduction, artificially inflated prey numbers, and increased hunter opportunity.

Developing a Preserves Regulation – 2015 Rule

By 2014, the National Park Service, after trying to use the compendium process to influence wildlife regulations locally in selected national preserves, decided that a federal regulation would be the best way to deal comprehensively with its concerns. In the last year of the Obama Administration, under Interior Secretary Sally Jewell and Alaska Regional Director Bert Frost, the agency put out its first Draft regulation to regulate Hunting in the Preserves, RIN1024-AE21.

DCC encouraged public comment approving this regulation (click here to read our comments). A final regulation was published in November of 2015. This 2015 Rule banned the hunting of wolves and coyotes in the denning season, den-hunting of black bear sows and cubs, bear baiting, shooting of swimming caribou, and hunting of black bears with dogs. It also established the authority and obligation of the National Park Service to manage wildlife on its lands consistent with ANILCA, its Management Policies, and the Organic Act.

Critics were quick to decry the 2015 Rule, using terms like “subjugation” and “federal overreach.” Litigation against the rule proceeded, with the State of Alaska filing a lawsuit in District Court against the Department of the Interior in January of 2017, joined by the Safari Club International and the Alaska Professional Hunters Association. DCC joined several intervenors (including Alaska Wildlife Alliance, National Parks Conservation Association, Defenders of Wildlife, Sierra Club, Wilderness Watch, Northern Alaska Environmental Center, and others) in defense of the Department of Interior.

In reality, the greatest hunting impact of the 2015 Rule was probably the bear baiting prohibition and to a lesser degree the wolf hunting season limits, as most of the other activities (such as den-hunting black bears and shooting swimming caribou) occurred in limited areas of the state, and their traditional practice by federally qualified subsistence users was protected. The key importance of the 2015 Rule was that it affirmed the authority of NPS to regulate wildlife harvest in the preserves according to ANILCA and Organic Act directives.The great majority of hunting and trapping activities on the preserves continued without prohibition under the 2015 Rule. This rule had five years of implementation without serious impacts either to wildlife or to hunting opportunity.

Change of Administration, Change of vision – 2020 Rule

In the early days of the Trump administration, it became clear that the Department of the Interior possessed a far different perspective on NPS authority to regulate wildlife management in the preserves than the previous administration held. In his January 17, 2017 confirmation hearing before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee (Chair, Lisa Murkowski, AK), Ryan Zinke, soon to become Secretary of the Interior, committed to a review of the rulemaking. He later confirmed the new administration’s direction in a couple of Secretarial Orders, 3347 and 3356, which emphasized deference to state regulations on federal lands, and support for hunting/shooting sports. Overall, the Trump administration appeared more open to influence from hunting groups such as Safari Club and less likely to act on its ANILCA and Organic Act Directives.

In May of 2018, the feared-but-expected roll-back of the 2015 Rule came in the form of a Draft Regulation (RIN:1024-AE 38) and EA. The regulation fundamentally questioned federal authority to regulate wildlife harvest on the preserves, and rolled back all the bans enacted in the 2015 Rule. DCC read the Draft Reg/EA and encouraged public comment. In the midst of this process, Secretary Zinke issued a Memo on September 10, 2018, ordering federal agencies to defer to state hunting and fishing regulations whenever possible.

Interest in this regulation was widespread, and the comment period was eventually extended to November 5, 2018. Over 400,000 comments were received from throughout the country. Click here to see DCC’s comments. After nearly two years of deliberations, NPS released the Final Rule/EA on May 20, 2020, in the closing months of the Trump administration. By this time, David Bernhardt had taken over as Secretary of the Interior, and the Alaska Regional Director Bert Frost had moved to Omaha, Nebraska to lead the Midwest Region office. Acting Alaska Regional Director Don Striker signed the Finding of No Significant Impact for the EA, supporting the undoing of NPS wildlife management authorities on the preserves. The 2020 Rule took effect on July 9, 2020.

DCC again joined several local and regional conservation groups on August 26, 2020 in a lawsuit brought by Trustees for Alaska asking for declaratory and injunctive relief from the 2020 Rule (Press Release here). It was our hope that if the Court ruled in our favor the Interior Department would be required to return to the 2015 Rule. In answer to our litigation, the Safari Club, Alaska Professional Hunters Association, the Sportsmen’s Alliance Foundation, and the State of Alaska intervened in defense of the 2020 Rule.

Political winds change again – 2024 Rule

We were hopeful that the administration of Joe Biden would find a way to promulgate a new rule, similar to the 2015 Rule. Or, perhaps a new Rule would not need to be promulgated, if our litigation achieved injunctive relief (vacatur).

We did not get the complete legal relief we’d hoped for. US District Court Judge Sharon Gleason ruled on our litigation, Alaska Wildlife (et.el.) vs. Haaland (now-Interior Secretary Deb Haaland), on September 30, 2022. In her ruling, Gleason found aspects of the 2020 Rule arbitrary and capricious, especially its conclusion that NPS must defer to state hunting regulations. She also found that NPS (in 2020) disregarded public safety concerns associated with bear baiting. She did not find adequate administrative justification for all the potential NPS bans that we advocated. She remanded the Rule to NPS for a re-write. A copy of Gleason’s decision can be accessed here.

A New Rule was coming soon. In January 2023 the National Park Service put out an Environmental Assessment (EA) with a preferred alternative advocating a regulation similar to the 2015 Rule. The Draft Rule, RIN 1024-AE70, would confirm NPS authority to regulate and would restore the bans. The comment period was extended to March 17, 2023 and DCC submitted comments (read here). We continued to await a prompt Final Rule in 2023, but months went by with no Final Rule. It seemed that NPS was taking a long, hard look at its Draft Rule, giving careful consideration to Judge Gleason’s ruling.

After more than a year the Final Rule, RIN1024-AE70, Alaska: Hunting and Trapping in National Preserves, was published in the Federal Register on July 3, 2024, and became effective on August 2, 2024. It was substantially different from the Draft in excluding most of the hunting bans except for bear baiting. While at first very disappointing, the decision became more palatable upon reflection. In the text of the Final Rule, NPS stated, “Information from user groups, including Alaska Native entities, that commonly harvest wildlife in national preserves in Alaska expressed their belief, consistent with NPS management observations, there is little to no demand to engage in these harvest practices in national preserves (other than limited demand to bait bears primarily in a single preserve). The practice of bear baiting, however, poses significant public safety concerns, which urgently requires regulatory action. Concerns with the other practices do not carry the same degree of urgency. They are either already prohibited by the state or occur on a limited basis.” To read the entire 2024 Rule, click here.

Present and future under the 2024 Rule

The most important part of the 2024 Rule is restoration of the authority of the National Park Service, under ANILCA and the Organic Act, to manage wildlife on its preserves and not to defer preferentially to the state regulations. The 2024 Rule, in banning bear baiting, regulates the most potentially dangerous and damaging hunting practice in preserves. And finally, the 2024 Rule clarifies the definition of trapping to include only those activities associated with traps and a trapline, not hunting activities that could be conducted under a trapping license. This does not prohibit a trapper from using a firearm to dispatch wounded animals, but would prevent land-and-shoot killing under a trapping license, something that has been permitted in Alaska.

At this writing, we have not heard of any litigation challenging the 2024 Rule. We are hoping that this Rule will survive the political winds that may blow over the next months and years. It is based on a solid foundation and has confined the bans to the most easily defended federal actions on the preserves. The 2024 Rule states, relative to the practices it did not ban, that “…park superintendents have authority to prohibit or restrict these practices if they deem it necessary.”

Still, there is much work to do in convincing Alaska legislators, agencies, and Board of Game members that federal and state collaboration and cooperation are goals worth achieving and that we can live together under these separate mandates.

We’d like to thank the law firm Trustees for Alaska for their generous assistance and pro-bono support of our involvement in litigation on the Preserves Rules. Special thanks to attorneys Michelle Sinnott, Katie Strong, Valerie Brown, Brian Litmans, Rachel Briggs and Joanna Cahoon.