DCC supports new hunting & trapping regulations for Alaska Preserves

Lead photo by NPS

UPDATE: Read DCC’s full comments on the proposed rule. ALSO Read DCC’s comments on the accompanying Environmental Assessment.

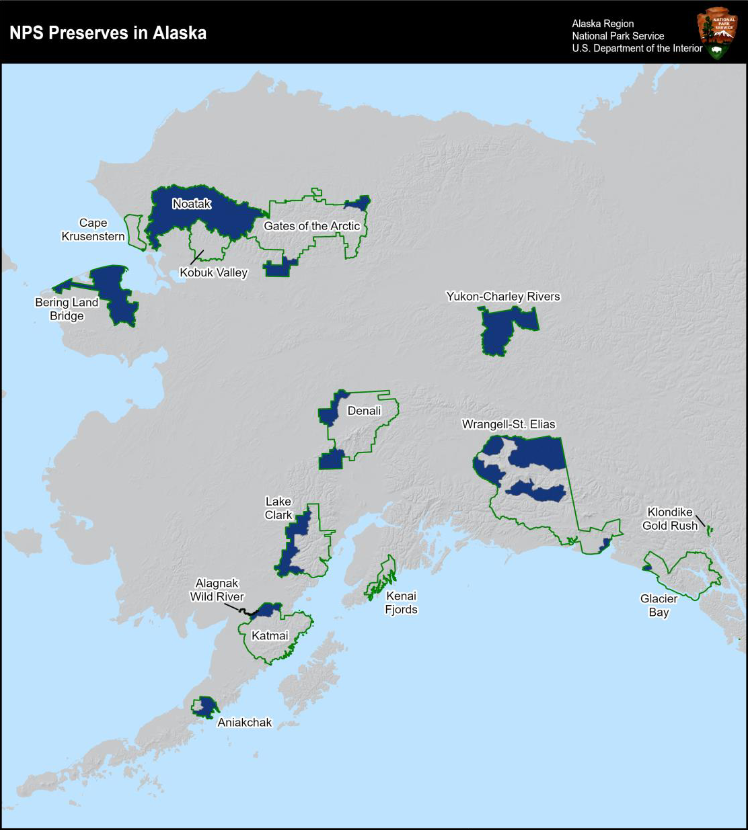

On January 9, the National Park Service published a rule amending hunting and trapping regulations for the National Preserves in Alaska, including Denali National Preserve. If this issue sounds familiar, that is because this is the third such rule on the topic to be offered since 2014, as successive Democratic and Republican administrations reverse each other’s course on responding to controversial State of Alaska hunting regulations. The new regulation restores the rule finalized in 2015 under the Obama administration and reverses the reversal during the Trump administration (2020), which sought to harmonize federal policy with that of the state. It is accompanied by an Environmental Assessment. Both are open for public comment until March 27, 2023 (UPDATED comment deadline after NPS extension).

DCC supports the new rule, and offers the following talking points as well as our full comments to the National Park Service. You may read and comment on the Proposed Rule at this link and the Environmental Assessment here.

Here is some context to help inform your comments.

Background

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) established Denali National Preserve and other Alaska National Preserves in 1980, and specified they should be managed just as national parks except that “hunting for sport purposes and subsistence uses, and trapping” are allowed.

ANILCA, the NPS Organic Act, and NPS Management Policies make it clear that the first duty of NPS is to protect natural ecosystems and processes, including the natural abundances, diversities, distributions, densities, age-class distributions, populations, habitats, genetics, and behaviors of wildlife. ANILCA gives NPS the authority to regulate hunting to achieve protection of wildlife.

While the National Park Service took over management of subsistence hunting in park units in 1990, the State of Alaska continued to manage other hunting on federal lands where allowed. However, the Alaska Board of Game – which sets state policy for hunting and trapping – became increasingly radicalized during the 2000s and began to authorize practices that alarmed park managers and wildlife conservationists. These included such practices as using bait stations to hunt bears, taking black bears and cubs in dens with artificial lights, and harvesting swimming caribou.

In 2015, the National Park Service emphasized that many of the state-authorized practices were designed to reduce populations of predators, and were thus contrary to the purposes of National Preserves and NPS policy. The State argued that its rules were not part of its predator control programs, but NPS was able to point to much of the testimony around the adopted rules to demonstrate intent.

The NPS 2015 rule prohibited specific objectionable hunting practices and sought to generally prohibit State rules that “are related to predator reduction efforts.” The rule included a few other provisions including a prohibition on interfering with hunting and trapping activities.

The NPS 2020 rule revoked only the prohibition of specific hunting practices and the general prohibition on predator reduction activities established in 2015. The justification for the new rule did not really address the arguments made in 2015 regarding the purposes and priorities of the National Preserves, but instead simply accepted at face value the State’s assertions that the authorized activities had nothing to do with predator reduction, cited the directive of the (Trump-appointed) Secretary of Interior to align federal hunting rules with those of the states, and noted that a similar rule adopted by the Fish and Wildlife Service had been overturned by Congress in 2017 under the Congressional Review Act.

The flimsy justifications for revoking the rule led to a lawsuit filed by the Trustees for Alaska on behalf of Denali Citizens Council, National Parks Conservation Association, the Northern Alaska Environmental Center, and a host of other conservation organizations. The lawsuit is still in process, but this new regulation would likely render it moot by replacing the objectionable portions of the 2020 version.

Proposed Rule

The proposed rule for 2023 does the following:

- Restores the list of specific prohibited practices from 2015 word-for-word. See Table 1 below for a complete list.

- Restores the prohibition on predator reduction activities in a more general way, the language reading: “Actions to reduce the numbers of native species for the purpose of increasing the numbers of harvested species (e.g., predator control or predator reduction) are prohibited.” Unlike in the 2015 rule, there is no proposed mechanism for identifying these actions.

- Clarifies that the term “trapping” means taking furbearers with a trap under a trapping license (the prior regulation left open the possibility of taking furbearers with guns or other means if allowed under a state-issued trapping license).

- Restores definitions for big game, cub bears, fur animals, and furbearers that were eliminated in the 2020 regulation.

NPS strengthens its justifications for eliminating particular hunting practices in the new regulation. State-authorized activities are prohibited for one of three reasons:

- Public safety, and the hazards of food-conditioned bears (specifically bear baiting).

- Consistency with “sport purposes” (for example, addressing the issue of shooting swimming caribou).

- Disallowing predator reduction/predator control activities as inconsistent with park purposes and NPS mandates.

An important issue within the debate has been the interpretation of “sport purposes,” which none of the regulations have sought to explicitly define. NPS asserted in 2015 and in the 2023 proposed regulation that “sport purposes” carry the values of fairness and fair chase. The 2020 rule claimed the term “sport” was only used to distinguish forms of hunting that are not “subsistence.” The State of Alaska does not distinguish sport hunting in any way; it just manages for “hunting” and claims that the permitted practices are important for state residents who do not qualify as authorized subsistence users, but are nonetheless just trying to obtain meat for food. But burbling around below that argument is the reality that both Alaskan and out-of-state hunters who engage in hunting purely for recreation – not need – take advantage of the same rules.

Please express your support for the proposed regulation at this link. Again, comments are due March 27 (updated). DCC’s initial talking points are at the top of the post.

If you have specific concerns about environmental impacts, be sure to comment on the Environmental Assessment .

Here is the table of specifically-prohibited hunting practices.

| Table 1 | |

| Prohibited acts | Any exceptions? |

| (1) Shooting from, on, or across a park road or highway | None. |

| (2) Using any poison or other substance that kills or temporarily incapacitates wildlife | None. |

| (3) Taking wildlife from an aircraft, off-road vehicle, motorboat, motor vehicle, or snowmachine | If the motor has been completely shut off and progress from the motor’s power has ceased. |

| (4) Using an aircraft, snowmachine, off-road vehicle, motorboat, or other motor vehicle to harass wildlife, including chasing, driving, herding, molesting, or otherwise disturbing wildlife | None. |

| (5) Taking big game while the animal is swimming | None. |

| (6) Using a machine gun, a set gun, or a shotgun larger than 10 gauge | None. |

| (7) Using the aid of a pit, fire, artificial salt lick, explosive, expanding gas arrow, bomb, smoke, chemical, or a conventional steel trap with an inside jaw spread over nine inches | Killer style traps with an inside jaw spread less than 13 inches may be used for trapping, except to take any species of bear or ungulate. |

| (8) Using any electronic device to take, harass, chase, drive, herd, or molest wildlife, including but not limited to: artificial light; laser sights; electronically enhanced night vision scope; any device that has been airborne, controlled remotely, and used to spot or locate game with the use of a camera, video, or other sensing device; radio or satellite communication; cellular or satellite telephone; or motion detector | (i) Rangefinders may be used. (ii) Electronic calls may be used for game animals except moose. (iii) Artificial light may be used for the purpose of taking furbearers under a trapping license during an open season from Nov. 1 through March 31 where authorized by the State. (iv) Artificial light may be used by a tracking dog handler with one leashed dog to aid in tracking and dispatching a wounded big game animal. (v) Electronic devices approved in writing by the Regional Director. |

| (9) Using snares, nets, or traps to take any species of bear or ungulate | None. |

| (10) Using bait. | Using bait to trap furbearers. |

| (11) Taking big game with the aid or use of a dog | Leashed dog for tracking wounded big game. |

| (12) Taking wolves and coyotes from May 1 through August 9 | None. |

| (13) Taking cub bears or female bears with cubs | None. |

| (14) Taking a fur animal or furbearer by disturbing or destroying a den | Muskrat pushups or feeding houses. |